Looks at advantages and limitations of the Latin American experience of workers trying to overcome capitalist work relations through their control of their workplace. By Henrique T. Novaes [*]

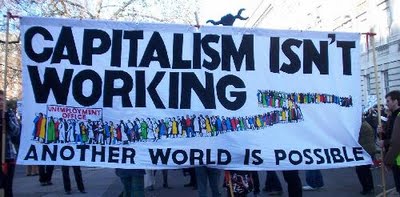

The destruction of the welfare state in Europe and the continuation of the state of social ills in the rest of the world are the consequences of an irrational society. In Spain, Portugal and Greece 40% of young people are unemployed and the state has unpayable debts. After riots in England’s capital city the Government insisted on calling the youth “vandals without a cause”, dismissing out of hand the obvious social causes of the revolt. Stratospheric public debts, neo-fascism, unemployment, underemployment, the return of hunger and poverty to Europe: words which keep appearing in a region which managed to create a restrained, partly nationalised – but capitalist nonetheless – capitalism in the 1945-73 period.

Capitalism under the hegemony of finance, turbo-marketisation and the return of primitive accumulation can only survive with increasing repression and the criminalisation of social movements. To cite a Latin-American example, Argentinian society reacted to the process of financialisation of its economy in 2001, a financialisation which gained strength after the military coup of 1976, throwing the country’s popular movements into the dust. In 2001 they did fight back, saying “Enough! Out with the lot of you!”: it was a symptom of the tiredness of neoliberal reforms and the neocolonisation of Argentinian society. However, the popular revolt of 2001 rapidly transformed into a new politics of ‘development’ under President Kirchner.

Capital’s irrational response to this global crisis – if not a catastrophe – once again pose us the challenge of building a self-managed socialism. History has already shown that self-management is possible. Marx showed us in numerous works of his that it is possible to build a society without classes or bosses, overcoming the wage-system and the state. Innumerable examples in Latin America in the twentieth century allow us to say that a DIY kind of unalienated work is possible and necessary. Similarly, an uncommodified kind of leisure and decent transport such as is not allowed by the demands of making profits. In other words, the activity of work can have a social meaning, with growing degrees of social control of production and the reproduction of material life. Equally, overcoming workplace hierarchy and the urgent necessity of global coordination of production by freely-associated producers are important themes for this millennium.

The collapse of “actually-existing socialism” in Eastern Europe must also be understood. Even if there were substantial advances at first, the experience degenerated. For Mészáros, the USSR created a society that was “post-capitalist but not post-capital”. The workers challenged for control of the means of production, but a body separate from the workers made the strategic decisions for society: how and what to produce and for whom, reproducing capital under a new cloak.

Equality

Indeed, I believe that self-management is necessary as an all-encompassing principle. Such counter-systemic struggles, unlike those for immediate improvements, can contest the pillars of capital and in some form embody in embryo the future society, beyond capital. To give an example, the Mulheres Camponesas (Peasant-Women) in the Rio Grande do Sul collectives contest the family hierarchy, insofar as these women “don’t want to have to wash our husbands’ pants any more” and avoid the re-establishment of patriarchy in their co-operatives. However, as Maria Orlanda Pinassi has shown, the struggles of these working-class women engage with, but also go beyond feminism: they also address environmental concerns, but go beyond this; and address the question of class, but also go beyond this.

In some workplaces taken over by the workers, there has been an overcoming of the capitalist division of labour, insofar as knowledge, previously in the hands of the few, can itself be socialised. Dependence on technicians’ expertise and the – complex – work they do can be overcome in some degree. Here, again, it is important to remember how in the 1974 Portuguese Revolution technicians helped go beyond the Taylorist planned organisation of work as a life-philosophy.

In some workplaces taken over by the workers, there has been an overcoming of the capitalist division of labour, insofar as knowledge, previously in the hands of the few, can itself be socialised. Dependence on technicians’ expertise and the – complex – work they do can be overcome in some degree. Here, again, it is important to remember how in the 1974 Portuguese Revolution technicians helped go beyond the Taylorist planned organisation of work as a life-philosophy.

In the most advanced cases, it even results in going beyond the wage-system, through the principle of “from each according to their ability, to each according to their need”. In other cases there is a narrowing of wage-differences and the creation of funds either to support the struggles of other workers, or to allow some workers funds to go to university, to pass on end-of-year surpluses, etc.

Indeed, it is important to point to the example of one Argentinian factory taken over by workers where they created a fund to improve the wages of workers who faced greater costs because of their kids. This reminds us of the principle of “substantive equality” developed by Mészáros based on the writings of Marx and the French socialist Babeuf. To express his argument, Mészáros turns to this paragraph from Babeuf: “Equality must be determined according to the capacity of the worker and the needs of the consumer, not by the intensity of work or the pure quantity of goods to be consumed. A man with a certain strength, when he lifts a weight of ten pounds, works as much as another man with five times his strength who lifts fifty. Just as he who satisfies a desperate thirst with a jug of water is enjoying no more than his less-thirsty friend who drinks barely a glass. The objective of communism in question is the equality of labour and pleasure, not of wages and consumption”.

I believe that this principle can also help orient the struggles of the most advanced feminist working-class women’s movements, along with other social movements which try to introduce the principle of substantive equality. On this point, I will recall an example given by the members of the Coletivo Usina (a group of social scientists and planners who gave advice and help to social movements). They said that in one project they wanted to divide their work equally amongst all of them. Then they realised that since they had elderly and disabled members and workers with other problems, they could not all offer the “same” labour output. Hence Babeuf’s example.

Equally, in the most advanced cases of workplaces taken over by their workers, the co-operative members do everything to avoid unequal conditions for agency staff, or indeed, fight for them to become co-operativists too. It is important to note this phenomenon insofar as a reasonable number of worker-controlled enterprises do take on agency staff: for me, a symptom of their degeneration.

Pillars of anti-capitalism

struggles at the Zanón and Flaskô self-managed factories embody class struggle, a fight against trade-union partnership with the state, and the possibilities of building class struggle in today’s Argentina and Brazil. In the case of Zanón, they take as points of principle countless pillars of anti-capitalism: rotating any positions of responsibility amongst themselves and making officials recallable; uniting and internationalising working-class struggles; changing gender relations in the factory; starting a new relationship with intellectuals and academics; the need for the demarketisation of production and overcoming Taylorist or Toyotist models of organising work. Ultimately, it is a matter of confronting alienated work, even if within the strict confines of today’s capitalist-crisis barbarism, and with countless contradictions.

More cautiously – and here we stand on more difficult ground – we can say that some social movements challenge the commodity-production system and are creating solutions to achieve demarketisation. For example, the schools run by Brazil’s Landless Rural Workers’ Movement (MST) show how people want an education system that is beyond capital, overcoming the intellectual poverty promoted by the country’s education policies. Such community schools daily challenge us to think of ideas of pedagogy which bring schooling itself into working-class struggle, building for the idea of collective work and not separating theory from practice in the production of healthy, non-marketised food, as well as the development of a culture of self-management and an understanding of social reality in all its complexity. The struggles at Flaskô – providing demarketised food; the struggles for free oil; the struggles of some of the worker-occupied workplaces of Latin America to control the labour process and establish shop-floor workers assemblies; and the Landless Rural Workers’ Movement’s challenge to ownership of the means of production; all touch on vital questions for social movements against capital in the twenty-first century.

The “expropriation of the expropriators” (Marx) or the “Return of the snail to its shell” (title of a recent book) is an urgent task, but beware: it could leave the alienation of work unchallenged. Equally, there is a great need to bring together all struggles against capital. They must combine and articulate their most immediate needs together with the need to overcome the capitalist move of production, completely transcending the orbit of capital. To this end, the coming-together of workers of different sectors and serious critique is vital. It is this which the Zanón and Flaskô are in some measure bringing about.

Julio Mella, a young Cuban Marxist who helped the struggle to revolutionise universities in his country, once said that “Win, or serve in the trenches for others. Even after we die we are useful: none of our work is lost”. Mella, even after his brutal murder, is still useful to us in this twenty-first century. He is still alive. He helps us to renew the development and creation of the camp of self-managed socialism, again grasping hold of the classic argument to advance revolutionary theory and practice. Self-managed socialism is a possible, necessary and urgent task.

[*] Professor at FFC-Unesp-Marília.

Translate by The Commune. Original at http://passapalavra.info/?p=46437.