There are many preconceived ideas, widespread and entrenched on these campaigns. Whom it lived, so it only witness what happened. By Manuela de Freitas

In April 1974 the fascist regime in Portugal was overthrown by the Armed Forces Movement (MFA), with the ensuing collapse of the old state apparatus unleashing two years of militant working-class struggle, with sharp antagonisms even within the army. The new organs of collective democracy established in towns, villages, factories and other workplaces during this ‘Carnation Revolution’ pointed to the possibility of radically reorganising society — but the workers’ movement was eventually subdued by state-socialist parties and their allies among the army generals. This Passa Palavra article looks at the efforts of those who tried to combine radical culture with participatory democracy.

by Manuela de Freitas

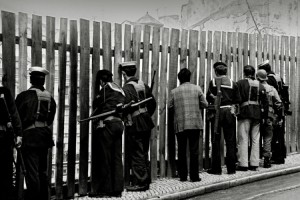

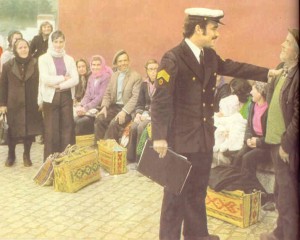

The army vans went out from Lisbon, carrying MFA soldiers and the actors. Upon arrival in each city they set up shop for one or two weeks: each day they went to towns and villages in the area where they were based, setting up the stage and preparing the seating for the audience. They went out in the villages calling on people – at home, at the cafés, in the streets – talking with them and getting them to come to that evening’s meeting. These ‘stars’ never knew for sure what attracted the people’s attention: the protagonists of the shows, or the protagonists of the Carnation Revolution.

When the show ended, the political debate began. The audience started off discussing the play with the actors, and then the solders would explain who they were and what they were there to do: after having freed Portugal from fascism, they wanted to know what exactly to do to rebuild the country and improve the people’s lives. They answered questions, took notes, and listened to the worries, hopes and fears of the people: “We need a new cemetery build because the nearest is 20 kilometres away, and in winter when we take one of us for burial, another two or three might die on the way…”. “We need a bridge”. “A road would do it”. “Build schools so we can learn to read”. “What are we going to do to the bosses?”. “Are we going to clean out all the fascists?”. “You lot have the guns, how can you guarantee us you’re not going to be even worse?”

The actors and soldiers returned to their base late at night, to go onto the next village and do the same the following day. Such were the first three campaigns, in 1974 and early 1975.

The Armed Forces Movements built the cemeteries, the roads and the bridges. But, little by little – weighed down on by the heritage of 48 years of fascism, backwardness, scarcity, social problems and bureaucracy – drained their lofty ambitions, and frustration at the realisation of their total absence of political experience set in. The generous efforts of the “liberators” gave way to apprehension and the pessimism among those “responsible for carrying out the promises of April”. They admitted beginning to understand that guns alone were not enough to achieve the difficult task – which the people expected of them, because they had promised it – of building a new Portugal. For this reason it was necessary for those with experience and talent in such matters to support them: the Portuguese Communist Party seemed to them to be the only left force with sufficient powerful organisation and political training to help them.

For this reason the PCP increasingly took over and controlled the 5th Division (the section of the MFA charged with the ‘Cultural Change Campaigns’). One group of actors began to feel uncomfortable in these circumstances – because they did not accept censorship of their programmes; because they refused to work under conditions which they felt undermined the quality and public enjoyment of their work; because in the discussions they took positions different from those held by those who now thought-on-behalf-of-the-people… and, of course, because they did not support the PCP – and returned to Lisbon in the middle of the fourth campaign. They were never asked to take part again.

What followed was an deliberate, carefully organised effort to discredit, politically and culturally, the Cultural Change Campaigns: “the MFA soldiers went around the country lecturing the people, politically colonising them, backed by little groups in Lisbon who, with total disrespect for communities’ own cultures, forced upon them artistic values which they refused because they were totally alien to them”.

This version of events was everywhere oft-repeated for two years by PCP activists, couched in either cultural or political terms depending on who it was directed at. For this reason, whether thanks to bad faith, sectarianism, envy or simple ignorance – fertile territory for it to sink roots – this version of events became accepted as fact.

It is difficult to find anyone who does not repeat this story today. Francisco Martins Rodrigues (who was one of the most prestigious and influential of leftist thinkers) wrote that “In reality, the “popular power” committees which later came under the control of officialdom, continued along the same lines as the “cultural change” campaigns whcih went from province to province telling people what was good for them. It was a sub-liminal repeat of the “psycho-social action” campaigns in Africa[n colonies]“

If those involved in the experience did indeed have malign intentions and what happened was ultimately an unwanted diversion which escaped the control of those who promoted it, maybe credible historians will find documentary evidence for this… But if, despite the best intentions of those who took part, it was not the best way of doing things, we can only hope that political tinkers will critique it, and from their analysis of the experience lessons draw lessons for the future. Those who lived through it are quite ready to bear witness.

Translated by The Commune. Original at “As Campanhas de Dinamização Cultural (1974-75)”.