By Caio Martins and Leonardo Cordeiro [1]

“If the fare increases, the city will stop” warned posters scattered a month earlier calling for mobilization in early June. The first demonstration takes place on a Thursday and it raids the city routine by blocking a downtown avenue with burning tires. Surprised and disoriented, the Military Police[2] cannot effectively repress it and, as protesters disperse and regroup, the confrontation spreads over a growing radius, prolonging the battle through the night. Repression and confrontation news spread and the movement calls for another demonstration the next day, in which five thousand people march on one of the largest expressways of this metropolis without conflict with the police.

This could be the description of the first moments of the struggle against the fare increase in São Paulo in 2013, but it is also the exact narration of the fight against the increase in Vitória, State of Espírito Santo, in 2011. The script similarity is no coincidence. It reveals the existence of a common strategy built by these movements over the last decade, which has at its core the popular revolts against fare increases.

Each year, mobilizations against transportation tickets fare increase have proved to be more and more central to urban struggles. From medium-sized cities to large metropolises all over the country, a struggle culture has been built in which every attempt to raise prices is answered by protests. These may have been, for a long time, the few street demonstrations organized by the left-wing to gain so much echo and popular adherence that they always ended up greater than they had begun – although, of course, they were often repressed.

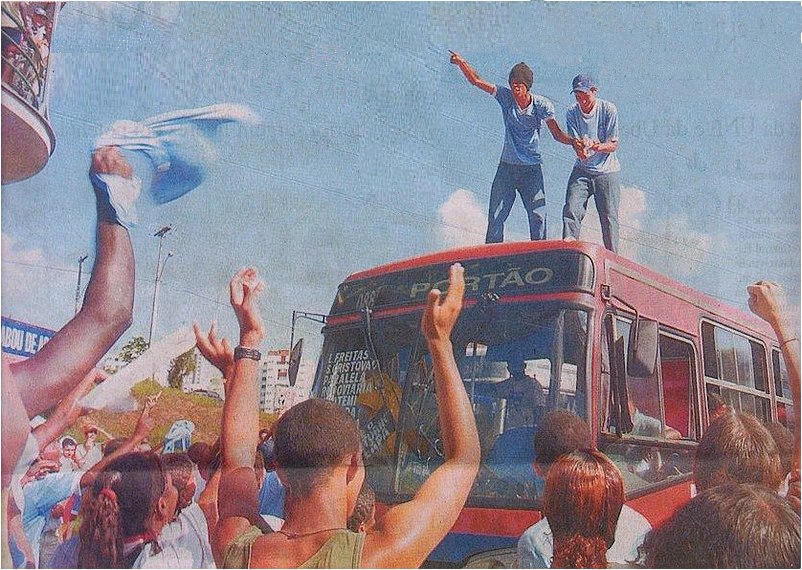

While the rise of other urban movements – housing, for example – hardly exceeds the limits of a defined territory or goes beyond the ranks of the organizations involved, in the fights against the fare increase, mobilization tends to take over the whole city, to be generalized as a revolt. Perhaps it is because transportation is not a problem restricted to a particular location or category, but an issue that permeates the life of every city. The suffering experience which concentrates on it is something faced jointly by workers, a common exploitation routine in which it is possible to recognize oneself (as class?). Out of a shared feeling, the revolt comes from transportation: it explodes, as a joint action, in buses set on fire, broken turnstiles or in occupied rails.

“Revolt” was precisely the name given to the events in Salvador in 2003 and Florianópolis in 2004 and 2005. Revealing the power of the path that was opening, the Revolta do Buzú (Bus Revolt) and the two Revoltas da Catraca (Turnstile Revolts) set the paradigm for struggles against fare rises of the last decade; they enter the militancy imagery as the transport mobilizations horizon. By stating explicitly that it was necessary to “repeat [what happened in] Florianópolis here” or simply by mirroring itself in that form of struggle as a diffuse reference, movements from diverse cities of the country perceive in these experiences the culminating outcome to be achieved. Thus, they tacitly trace the same fight strategy, even though that is not always enunciated.

The emblematic itinerary that constitutes itself in Salvador and Florianópolis brings some elements that would repeat in countless cities in the following years, with or without success. The constellation of these elements composes the tactic we call here “popular revolt”: a short, but explosive, intense, radical and decentralized process. The first demonstrations act as a mobilization ignition that extrapolate the control of those who initiated it – which lose all the capacity to interrupt it. There is a direct action escalation: massive occupation and important city arteries blockade, police confrontation, public and private properties attacks, looting. By harming the circulation of value and launching a threat of chaos – widespread disobedience –, the protests, which do not respond to a representative with whom negotiation is possible, force the government to retreat in order to re-establish “order”.

Salvador and Florianópolis were successfully replicated in Vitória, Teresina, Porto Velho, Aracajú, Natal, Porto Alegre and Goiânia over the years, until the fares overthrow in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and more than 100 other cities in June 2013. Through the perspective of those who witnessed this last moment, specifically in São Paulo, this article aims to envision the whole process.

The revolt direction

The revolt direction

If, on the one hand, the guideline of “popular revolt” invests in the loss of control and explosiveness, on the other hand, it almost always depends on a highly organized struggle pole – an organization that elaborates and formalizes its meaning and guarantees some cohesion, allowing mobilizations to advance autonomously following the primary direction: a price raise revocation claim. According to the narrative assumed by the Movimento Passe Livre (MPL)[3], it was precisely because it did not have this articulated pole that the Revolta do Buzú was not victorious: the empty space was occupied by leaders of bureaucratized student entities and political parties. In Florianopolis, an independent youth organization formed by a split of a Trotskyist group of the Worker’s Party (PT) that merged with Indymedia anarchist militants would take on this role, devising a strategy to achieve victory. It was the Passe Livre Campaign – later named MPL – that, in the revolt of 2005, would fulfill, in the words of a former MPL militant, the role of a “good leadership”, that knew how to “play, compose and create with the practices produced in an autonomous way by social mobilization”:

When I speak of direction, I do not speak of command or obedience, nor of manipulation of the masses. I speak of a group that thinks, plans, discusses and studies the social issues around popular uprising, as well as the day-to-day of this uprising, in order to achieve the movement’s demands. Nonetheless, such a role of leadership becomes necessary on the assumption that, if left to its own dynamics, popular revolt probably would not be effective in achieving the accomplishments desired. This direction, this articulating, propellant and thinking group would therefore aim to increase the probability that popular revolt is reflected in the fulfillment or conquest of its claims. (…) with a certain social composition, the only effective, possible and desirable direction is not the one that tries to discipline, shape or control social behavior towards an ideal, but one that can find and put in a virtuous sequence the diverse – apparently antagonistic and spontaneous – practices that arise from social movement. [4]

That “group that thinks, plans, discusses, and studies” the social issues surrounding transportation and the struggles against fare raise during mobilizations will plan its steps on the streets “in order to achieve the demands” and, at times, it also assumes the role of producing the revolt, that is, of creating the conditions by means of mobilization, agitation and propaganda work, and impelling the first demonstrations. In the midst of the protests, the formalization built by the organized pole ensures the cohesion between diverse and even contradictory practices (from vandalism to “coxinhas”[5]), directing them towards a common target. This moment of control is essential to its opposite moment, the loss of control.

As struggles against fare raise burst in cities all around Brazil, several groups were formed to assume this directing role. Such a place would be especially occupied by the various “free-pass struggle committees”, which, in 2005, would articulate nationally, forming the MPL. The Free Pass Movement arises, thus, as the main organized expression of a broad social movement that precedes it and goes beyond it, formalizing around itself a common imagery of transport struggle (principles, proposals, tactics, history, aesthetics) shared by several other organizations and movements[6]. Born of the revolt enthusiasm, as an attempt to elaborate the meaning of these experiences, the MPL points, at the same time, beyond them, by questioning the fare and the current transport model. Moreover, it does not fail to focus mainly on the struggles against fare raise, in a permanent tension between the reactive dimension of these journeys and the construction of another transportation system. By these means, the national articulation for free pass takes, over time, the shape of an articulation between the leading groups on the struggle against increases.

The leadership role assumed in the revolt comes in contradiction with the principles of horizontality and autonomy, so dear to MPL. In the struggle against fare raise, therefore, its form can only be that of a direction which denies itself, which does not affirm itself as such, and sometimes does not even see itself as such; which does not aim at total control and, more than that, aims to lose control completely

Control and loss of control

June 2013 in São Paulo seems to be a moment in which the movement believes to have clarity on what to do in the course of the revolt and, thus, assumes the leadership role in the most conscious and visible way. The São Paulo’s MPL collective (MPL-SP) sets itself the task of elaborating alone a detailed planning of struggle, based on the dynamics that could be grasped from previous specific experiences: to be successful, it should be radical, intense and decentralized. There were no open assemblies or a broad front; articulations were extremely selective to avoid the wear faced in previous journeys. Everything that seemed unnecessary to the set guideline was left behind or discarded. The itinerary of each demonstration, decided by the restricted group of MPL-SP militants, was tactically secret: it was informed to some nearby organizations, but it was never revealed to the vast majority of demonstrators. And even though “popular revolt” and “loss of control” appeared in the movement’s public discourse on the very first day, that small group of people maintained, despite the rhetoric, a reasonable control over the demonstrations until the eve of the repealing of the raise decree. Even in the immense march of Monday, June 17, – which was attended by more than a million people, with no exaggeration – the group was able to carry out the route it had defined, dividing the act into two fronts that met again at the Estaiada Bridge, in spite of other divisions. Over the course of three weeks of fighting, the first time MPL-SP failed to conduct a demonstration along the route decided happened on the following Tuesday.

On June 18 and 19 the protests actually decentralized. Riot and loot scattered throughout the city. The Movement did not even manage to lead the beginning of the demonstration and it was impossible to know everything that was going on. While hundreds of thousands of people took Paulista Avenue and Consolação Street, São Paulo’s downtown became a kind of liberated zone: numerous looting at retail chains, a Record Television Network car set on fire, banks and shop windows destroyed. After knocking down the State Government Palace gate the day before, the demonstrators tried to invade the City Hall, destroyed its windows and sprayed graffiti on it. “Officials and advisors to the mayor get to arm themselves and erect barricades”[7].

Simultaneously, but off camera, autonomous demonstrations took place in various parts of the city outskirts. In the Esmeralda and Rubi lines of the CPTM (São Paulo Metropolitan Trains Company), upon malfunctions, passengers occupy the lanes, break the trains and sabotage the tracks. In Cotia, about five thousand people block both directions of the Raposo Tavares Highway. Protests block the Socorro Bridge and the M’Boi Mirim Road. In Grajaú, simultaneously to a looting wave, more than 80 buses were damaged. In the East Zone, the impact was so great that the East Autobus Consortium 4 placed less than half the fleet in operation on the next day. In Guarulhos, protesters block for hours the International Airport’s access, while in Parelheiros the population invades and paralyzes the beltway.

Violent and widespread, the order breakdown that occurs with the revolt’s outbreak brings with it a powerful glimpse of the possibility of social transformation. When describing this moment in Florianópolis, in 2004, a militant affirms that “the ultimatum given by the movement, the convocation of mega-manifestations and the widespread civil disobedience left the city in a trully pre-insurrectional climate”. His words could well refer to the last days of the struggle in São Paulo, almost ten years later: “It was difficult to predict what would happen (…) if the ruling class had not revoked the fare raise”; “The situation could escape completely the control of the constituted (and destituted!) authorities”[8].

General strike, public buildings occupation, the taking of the city by barricades in each neighborhood, fleet expropriation… these are some outcomes that the popular ascent opened to imagination on the eve of the fare raise revocation announcement. It is precisely the threat of a huge organizational leap from the workers that alarms the ruling class – “social chaos” knocks at the door and must be restrained by the government, yielding.[9] The historical tactic of the struggles against fare raise (which we call “popular revolt”) bets on such a threat for its success, but, at the same time, it depends on it not happening. To achieve the central claim, the revolt triggers an explosive process, which is necessarily braked at the moment of conquest.

If the tactic is efficient, the organizational leap is already born castrated and will exist only as a glimpse. The brief loss of power on the streets allows us to foresee another power, a popular power, as palpable as it was unattainable in those days. By existing exactly in the tension between a highly organized minority and an unorganized majority, popular revolt limits itself. At the same time that in the struggle against the fare raise in São Paulo population took direct action over their lives, it is no less true that there was a command that decided what to do. If, after June, a part of the left-wing judged that the problem in the process was the lack of a “revolutionary direction”, to us the matter seems to be the opposite: in the revolts against the fare raise, what lacks – and that is why it is about revolts – is horizontality, that is, direct power of those who were on the streets on what they were doing, something that depends on the existence of structures rooted in the everyday life of the workers.

Between government and misgovernment

In the words of a MPL-SP militant:

Certainly, June would not have happened the way it did if there had not been this group of people analyzing, making plans and busting their backs for them to be achieved. I’m sure of it today, but that was a limitation that stood for things to happen the way they happened in that context. It was a problem that only that group decided everything that was going to happen. It was a limitation that there were no neighborhood or workplace organizations that could intervene in what was happening all over the city. (…) One of the MPL’s objectives is the popular management of transportation, something that clearly this group could not accomplish, precisely because this can only happen if there were organizations in each neighborhood organizing transport themselves and not being organized by others.[10]

Such a limitation that was underlying the struggle is the very limitation of the historical context in which the revolts arise. Grassroots organising disappeared years ago from the political practice of the Brazilian left-wing. The popular organization that was its baseline was the very cost of the left-wing’s project of government conceived by it at the end of the 1970s. It was a price to be paid as this project was carried out: moving up towards the government, the PT carries with it popular movements and increasingly inserts them into the mechanisms of social conflict management (from governmental channels of “participation” to the expanding “Third Sector”). No wonder the speech’s keynote is that of inclusion. Marked by an increasing abandonment of direct action and framed by public policies – often developed from the knowledge accumulated by the own militants –, popular organizations suffer an emptying that ties them to a huge government machine[11]. At rank-and-file level there could subsist only objectified contingents of workers, duly registered and represented – treated as currency in the trading of bureaucracies.

The generalized feeling of powerlessness, rooted in the left itself, spreads among workers and finds chorus in radicals outside the government as well. Underpinned by clichés of a deterministic Marxism (whether it is a “realistic” analysis of the government or a leftist defensive opposition), the immobilizing consensus on “the forces correlation” naturalizes injustice and suffering: measuring forces against capital is a waste of time. A real domestication was carried out: “criticism”, in the words of Paulo Arantes (in whom we somewhat rely on in this analysis), is allowed “only if it is constructive and has the indication of its financing source.”[12]

“In this astonishing factory of consensuses and consents which the country has become”, the gears of inclusion are intimately linked to a project of “armed pacification”[13]. The institutional pieces do not work without the exception mechanisms: both complement each other in the endeavor to gain and manage individuals, divided into territories. With the unprecedented multiplication of social control technologies experienced by the country, there are “policemen who carry out activities of educators or social agents, (…) bank managers who function as business and entrepreneurship advisors, merchants who become bank tellers, community leaders who run government programs, public managers who transact private enterprises.”[14]

It was to be expected that the answer would come as a loss of control. For the small groups that remained on the left side on the margins of the government, to trigger the misgovernment of the revolt was the possibility of confronting that gigantic administration structure of the class struggle. The violent political explosion of the streets refuses the participation mechanisms and reacts to armed repression. In São Paulo, the tactics of the movement are assumedly elaborated to face the dialogue strategy expected from a PT City Administration.[15]

Although we still need to analyze the place of transportation in the city’s management structure and in its refusal, it is evident that revolt appears precisely as a destructive critique, as a denial of the immobilist consensus. An explosive and short-shot reaction, it responds to the left-wing government’s project within the logic that it imprinted on the social struggle: the spectacular, the mediatic time, the popularity decline. Revolt is perhaps the reverse of that immobility, the political translation of that feeling of helplessness – finally, a dissonance echoes in the monotonous paralysis chanted by the most varied political sectors. However, as a mere echo of the working class’ forgotten power, a glimpse of a real antagonism, revolt is limited. With one foot (or two?) in the politics of the spectacle, it can not go beyond impotence.

The meaning of the revolt

The apparent immediacy of the revolt, a time of immediate events, is also a deeply mediated time – mediated by a theater that runs separately from the everyday life. As the revolt tactic begins to direct the entire MPL’s strategic construction, that accelerated pace is transposed into the movement’s routine. Their efforts are recurrently summarized, thus, to the preparation of the mobilization, in a logic of “agitation and propaganda”. Although it exploits the playful and artistic dimension well, it often does not go beyond punctual, discontinuous, uprooted and dispersed interventions, characteristic of a certain activist tradition[16]. Without grassroots structures, the link between demonstrators and the organization is mediated, in the struggle against fare raise, almost exclusively by the internet, television and printed newspapers. Media’s centrality in MPL’s performance appears in the very origin of the movement, heir of the Indymedia Center (IMC) network, which was for many years its main mean of communication, later replaced by Facebook. In 2013, these media channels – mostly controlled by the ruling class – were the main means used by the movement to call the demonstrations and disseminate its claims and positionings.

The frailty of the link between the two poles permanently threatens the direction of the revolt: its meaning may be appropriated – and the media is in a privileged position to do so. So it happened in June 2013, when the bourgeois press, facing demonstration massification, worked to dilute the 20 cents claim in the midst of the diffuse evocation of corruption.

This loss of meaning haunts the loss of control. If mobilization should overflow MPL’s control, it must necessarily overflow the guideline constructed from the beginning by the movement. Therefore, each time it reaffirmed the unique meaning of the protests, the MPL reaffirmed itself as the direction of the process. Nonetheless, the glimpse of transformative power that the revolt allows us to have has to go far beyond the 20 cents – it is a force of total change. The revolt explosion is, therefore, also the explosion of meaning. And, as far as this explosion has to be restrained, the guideline maintenance (in which the MPL is committed to) will play a fundamental limiting role. After the ticket price reduction, a mobilization without direction remains, whose meaning will be easily disputed by the old intermediaries. However, the beyond-the-20-cents claim, which only existed in the fight for the 20 cents, is now nothing.

In June 2013, the process found its limit very strongly in São Paulo – precisely where the 20 cents clearly defined the direction of the revolt. Soon after, the ebbing of São Paulo’s mobilizations hits the cities where the demonstrations exploded due to the repercussion of the events spread by the media. Nevertheless, in places where the protests’ purpose was more dispersed, disaggregated, such as Rio de Janeiro, the end of the process was also diluted in a long blanching that lasted for the following months. Since the streets of Rio de Janeiro did not have a predominant meaning – the revolt was not a tactic planned by a leading group with a clear objective –, they do not completely lose meaning after the fare reduction.

June passed

The tactical elaboration of the popular revolt, which has been developed since 2003, was brought to its last consequences. The new path of the urban struggle that unfolded in different revolts against each fare raise in the country hits the top in June. Reaching an unprecedented dimension, the definitive success of the revolt as a tactic in 2013 is also the depletion of this same tactic.

In the struggles on the streets, it does not seem possible to dribble the repressive forces with the same maneuvers of the last years. Insistence on them draws a riot management scenario, already scattered throughout the world: even the most violent protests, routinely framed and surgically restrained by the police, are no longer so capable of shaking order. From intelligence services to justice, state repression improves its product.[17] Protests enter into the calculations of politicians, the press and the insurers. Clashes with the police, summed up as innocuous weariness, are as emptied as the model of “huge demonstrations” – organized by coalitions that do not get tired of seeking the banner under which “the left unity” will once again be forged. It seems that an obsession with the past has spread, which prevents from projecting on the horizon something beyond the mere repetition of what has already happened: “June is not over”, “August’s journeys (sic)”, “I’m on the street again”, “others Junes will come”… and so on. The street as an end itself is a dead end. An arena where the symbolic dimension has hypertrophied, in which we witness the protest-for-the-protest barren show, not too far from violence-for-the-violence: what matters is “to dispute the imaginary”.[18]

And it was not only in one of its poles (the street) that the revolt tactic burned out; the same happens with the other (the organized collective): detached from the mobilization process, the group that took the role of leadership loses its sense of being. When the fare drops in São Paulo and other hundreds of cities, the organizational form of the revolt direction against fare raise completes its endeavor, which was designed each year: to open a crack in the consensus. Oriented by and for the revolts, the format assumed by the MPL loses its place. Perhaps because of this, many of the groups that led great struggle journeys and achieved victories then sought to reformulate their performance. However, it is possible to see practices that indicate a strong tendency to insist on the old directing role.

On the one hand, that group that was linked to something much larger than itself turns to the maintenance of its identity and its structure: to continue existing, it isolates itself more and more from social struggles and its combatants, becoming closed in itself.[19] On the other hand, accelerated by the rhythm of events in the revolt, it blindly wastes its strength in the eagerness to respond to the growing charges of a political game in which it was recently considered an actor – including the interview and positioning requests, diverse manifest and action signing, academic research, panel and lecture invitations, public and private managers interests.[20] Recognition by other “political actors” transmits to the organization the dynamics of this theater. If it not capable of opening a new horizon for itself, it will inevitably clings to the past and reaffirms the dead form – only a symbol remains, a mark to be administered.[21]

Saying that the historical tactic of “popular revolt” is worn out is by no means to decree the end of the revolt – that attitude that has been pulsating for centuries among the dominated. On the contrary, it has never been so present: since June, disposition to conflict has only grown. But what do we build beyond this disposition? Millions took to the streets, but, when they went back to their homes, neighborhoods and workplaces, they returned to the suffering and humiliation routine (perhaps a little more outraged?). Although it has produced echoes, the mobilization moment could not go beyond itself, it did not find continuity in a moment of organization.

If we did not left 2013 with an enhancement on the organization of the ones from below, perhaps the land for this organization is now more fertile. By pointing to something alive beyond the dead day-to-day of consensuses and consents, June broke the spell. Nonetheless, it was still an impotent refusal: we barely foresee the possibility of another world. How to make what was glimpsed go from possible to real? It is at least indispensable to overcome the centrality of the revolt tactic and formulate a broader strategic perspective, the perspective of a more potent rejection, rooted in the everyday life. It is necessary to build what has become imaginable.

Footnotes

[1] Originally published at Passa Palavra (Revolta popular: o limite da tática). This is a revised version of the same text published in “Junho: Potência das ruas e das redes” (São Paulo, Fundação Friedrich Ebert, 2014). Translated to english by Nilen Cohen, revised by Clara Spalic and published at: https://libcom.org/library/brazil-popular-revolt-its-limits.

[2] Translation Note: In Brazil, the police is militarized. According to Wikipedia, “Military Police (…) are a type of preventive state police in every state of Brazil. The Military Police units, which have their own formations, rules and uniforms depending on the state, are responsible for maintaining public order across the country including the Federal District and its capital, Brasília. Deployed solely to act as a deterrent against the commission of crime, units do not conduct criminal investigations. Detective work, forensics and prosecutions are undertaken by a state’s Civil Police”.

[3] This is the narrative that appears, for example, in the article signed by São Paulo’s MPL in the book Cidades Rebeldes (São Paulo, Boitempo, 2013). Translation Note: This book was published in France under the name Villes rebelles (Paris, Éditions du Sextant, 2014) and MPL’s article can be read in Frech at: http://www.lcr-lagauche.org/a-lire-un-extrait-de-villes-rebelles/.

[4] Leo Vinicius. Guerra da Tarifa 2005, São Paulo, Faísca, 2005, p. 60-61.

[5] Translation Note: Pejorative term used at 2013 to refer to the pacifist protesters wich held national flags at the demonstrations. Before that, the term was popularly used to refer to Military Police agents. After 2015 anti-Dilma protests, it became a pejorative nickname for right-wing protestors.

[6] To mention a few examples: the Movimento Não Pago (Don’t Pay Movement) in Aracajú; the Public Transportation Struggle Bloc in Porto Alegre; the Belo Horizonte Zero Fare Campaign; the Movimento Porrada no Busão (Punch The Bus Movement) in Porto Velho; the Pula Catraca (Jump the Turnstile), Contra Catraca (Against The Turnstile), Transporte Justo (Fair Transportation) and Contra a Passagem (Against The Fare) movements in the countryside of São Paulo; among other countless committees, forums and struggle fronts scattered throughout the country.

[7] Elena Judensnaider and others, Vinte centavos: a luta contra o aumento, São Paulo, Veneta, 2013.

[8] Leo Vinicius, A Guerra da Tarifa, São Paulo, Faísca, 2005, p. 60-61.

[9] In the first Turnstile Revolt, the threat was explicit: “After almost two weeks of revolt, students gave an ultimatum and called a monster protest that would gather more than twenty thousand people. The movement leaked to the authorities that if there was no revocation of the ticket fare raise, they would try to occupy the town hall and the city hall by decreeing a municipal government by popular councils. Mix of bravado, strategy and ingenuity, the threat was effective. Faced with the imminence of a march of enormous proportions and unpredictable consequences, a federal judge in the city simply revoked the fare raise, just moments before the demonstration, claiming to fear the “social chaos” generated by the “battles on the streets of Florianópolis” in the fight against the ‘exorbitant prices attributed to the collective transport tickets'” (Pablo Ortellado, Um movimento heterodoxo, CMI Brasil, 2004, http://www.midiaindependente.org/en/red/2004/12/296635.shtml). In June 2013, just before the announcement of the fare raise revocation in Sao Paulo, the proposal to call a general strike for the following week echoed among the most diverse leftist organizations (the proposal even had consequences: such a strike happened, but as a farce, detached from the revolt).

[10] The comment is from comrade Arabel, published in a discussion group on a social network.

[11] The article “Estado e movimentos sociais” (in English: “State and social movements”) reflects more deeply on the relationship between left-wing government and social movements. In: http://passapalavra.info/2012/02/52448.

[12] Paulo Eduardo Arantes. “Fim de um ciclo mental” in Extinção (São Paulo, Boitempo, 2007), p. 250, among other articles and interviews compiled in the same volume, especially in parts 3, 4 and 5. See also “O ‘pensamento único’ e o marxista distraído,” by the same author (Zero à esquerda, São Paulo, Conrad, 2004). In a meeting with the movement in June, when São Paulo’s mayor “asks for the definition of a budget source of the subsidy they claim (…) the MPL says that it is not up to the movement to find technical solutions to a social demand” (Judensnaider, 2013). For a possible origin of the “propositional criticism” in the Brazilian left, see the note on Passa Palavra at http://passapalavra.info/2012/05/5/58422.

[13] We continue on Paulo Arantes’ trail, now with the essay “Depois de junho a paz será total,” in his last book O novo tempo do mundo (São Paulo, Boitempo, 2014).

[14] Livia de Tommasi and Dafne Velazco. “The Production of a New Discursive Regime About Slums in Rio de Janeiro and the Many Faces of Community-based Entrepreneurship”. Text presented at the 35th Anpocs meeting (Caxambu, 2011) and quoted by Paulo Arantes in “Depois de junho será a paz total”.

[15] In April 2013, during housing movement demonstrations, Fernando Haddad came down from the cabinet and addressed the protestors, turning the act into a rally. In the first major act of June, the City Administration expected to receive a commision of the movement, to put it, apparently, “in a dispersive technical negotiation table” (Judensnaider, 2013).

[16] The movement appropriated and developed different ways of agitating the city and propagandizing the struggle: activities in schools, pamphlets, bashing authorities, posters, tagging, catracaços (turnstile jumping), social network divulgation, media actions, small protests, articles and press reports, among others. For a more profound critique on the activist culture inherited by the MPL, see Felipe Corrêa, “Balanço crítico acerca da Ação Global dos Povos no Brasil” (published in six parts at Passa Palavra: http://passapalavra.info/2011/07/42773).

[17] For more on this scenario, see “Chaos Theory”, originally published in Police Reviews and translated by Passa Palavra into Portuguese (http://passapalavra.info/2014/03/92961) and “A mais-valia relativa da polícia: sobre repressão e controlo social” in the same website (http://passapalavra.info/2014/04/93676). It costs nothing to say that the police encapsulation tactic (Hamburger Kessel), a 2014 novelty of São Paulo’s Military Police, has been used since 2006 in Santa Catarina – not by chance, the state where Florianópolis is.

[18] Protesting and breaking seem to have been captured from their tactical dimension and framed within a purely aesthetic dimension. Articles report this: “Será que formulamos mal a pergunta?” By Silvia Viana (Cidades rebeldes, 2013), and “Agora só faltam 3 reais… e um imenso desafio” (http://passapalavra.info/2014/06/97065).

[19] No matter the size of this bureau, whether it is made up of four or forty people, since there is what Felipe Corrêa calls a “waste of social force”: “there is an excess of processes and structures, people doing what is not necessary, few people involved with important activities (grassroot work, for example) etc.” (“Movimentos sociais, burocratização e poder popular. Da teoria à prática. 3) Mecanismos e processos de burocratização” at http://passapalavra.info/2010/11/31590).

[20] This perverse moment in which “the social basis of struggle is no longer interested in the movement, but public managers do,” is often a moment of “internal crisis”: the militants “turn inward, try to discuss the shortcomings that led to it or at least to ensure what was left. Charges are exchanged, wear and disputes for power occur. These discussions are often of little interest to new people, which reinforces the isolation scenario and low participation.” See the article “Buro-ácrata”, by Grouxo and Legume (http://passapalavra.info/2014/04/94231).

[21] As it can be seen, for example, in a note published by the MPL national federation “On the Abbreviation Abduction”: http://saopaulo.mpl.org.br/2014/05/13/nota-da-federacao-nacional-do-mpl-sobre-o-sequestro-de-sigla/.